Somatic OCD is a subtype of obsessive-compulsive disorder that involves preoccupation with bodily sensations or functions. People become excessively focused on automatic or involuntary bodily processes, such as breathing, swallowing, blinking, or other sensory experiences.

Somatic obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or sensorimotor OCD, is an OCD subtype that involves obsessions about the physical sensations you can’t control. You might have thoughts like: If I don’t keep track of how many times I blink, I could blink too much or too little, and something bad could happen. If I don’t focus on my breathing, I might stop breathing or struggle to breathe. My heart is beating faster—what if I’m having a heart attack?

Living with somatic OCD can be extremely stressful and uncomfortable, but exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy is an effective way to manage your symptoms. Read on to learn more about the symptoms of somatic OCD, how it can affect your daily life, and how you can find treatment.

What is somatic OCD?

Like other forms of OCD, somatic OCD is characterized by a cycle of obsessions and compulsions. Obsessions are recurrent and intrusive thoughts, sensations, images, feelings, or urges.

Somatic OCD is often triggered by intrusive thoughts that lead to a hyperfixation on bodily functions, such as breathing, blinking, swallowing, heartbeat/heart rate, chewing, the movement/feeling of your tongue, bladder or bowel pressure, or itching. It can also involve concerns that something is wrong with a bodily function—like fearing you might forget how to swallow or blink, or that something might go wrong if you don’t pay attention to every detail.

These fixations create an ongoing preoccupation with automatic, involuntary processes, which can result in a compulsive need for distractions.

Find the right OCD therapist for you

All our therapists are licensed and trained in exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP), the gold standard treatment for OCD.

Somatic OCD obsessions

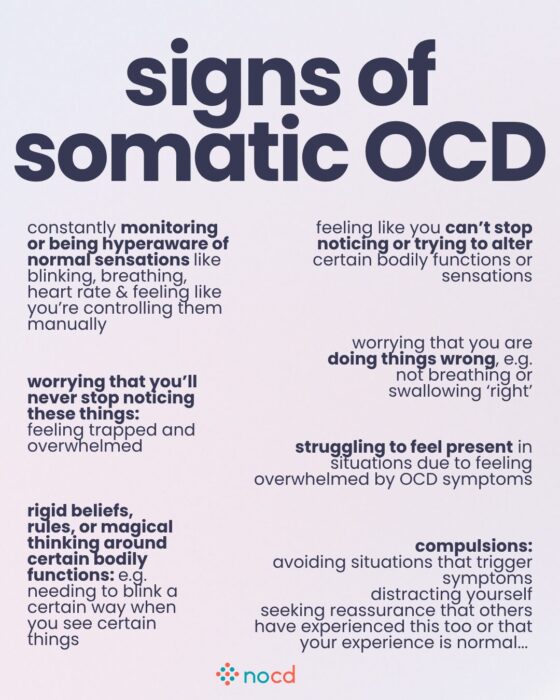

The symptoms of somatic OCD vary from person to person, but they involve obsessions surrounding one or more bodily functions, which results in high levels of distress, guilt, shame, or embarrassment.

Here are some common somatic OCD obsessions:

- “Why is my breathing so loud?”

- “I can’t stop noticing my breath.”

- “How often am I blinking? Am I blinking the normal amount of times?”

- “Am I chewing the right way? What if I forget how to chew?”

- “How do I know when to swallow? I’ve never thought about this, but now I’m worried I’m not going to swallow correctly.”

- “How many times is my heart beating every minute? I need to count.”

- “I can’t stop paying attention to my heart beating. What if I have a heart attack?”

- “I can feel my nose and I can’t stop focusing on how it moves when I talk. Why does it do that?”

- “My breath doesn’t feel deep enough. I’m not breathing correctly.”

- “Am I making eye contact when I’m speaking? I think so. But am I looking at the person I’m talking to, or looking away? Where are my eyes looking?”

- “How will I ever live a normal life if I can’t stop thinking about my breathing?”

- “What will become of my relationship with my partner if these thoughts don’t go away? Will I ever be able to feel present with her again?”

Community discussions

Somatic OCD compulsions

Compulsions will also vary depending on each person and which process or function their intrusive thoughts latch onto.

Here are some common somatic OCD compulsions:

- Distraction: You may try to distract yourself in an attempt to make your intrusive thoughts go away. You may try to immerse yourself in a movie, book, or exercise as an attempt to focus your mind on something other than your physical sensations. This is often unsuccessful and strengthens the severity of your intrusive thoughts.

- Excessive research: You may spend hours online researching your condition. You may search online forums for solutions to stop your intrusive somatic thoughts and to determine if your experience is normal.

- Mental review: You may find yourself thinking back to a time when you were free from these obsessive thoughts. You may feel nostalgia and ruminate on the time in your life that now feels inaccessible.

- Self-reassurance: You may try to reassure yourself that these thoughts are not a problem and that they will go away on their own. You might tell yourself, “Don’t worry. I’ll stop thinking about my breath eventually. It’s not such a big deal.”

- Reassurance seeking: You may turn to family or loved ones in an effort to make sense of your experience. You may ask questions like, “How often do you notice yourself breathing?” or, “Do you ever find that you’re unable to stop paying attention to your heartbeat?”

- Avoidance: You may avoid certain situations you feel will make your somatic OCD unmanageable such as eating in a restaurant with friends because you won’t be able to stop paying attention to your chewing. You may also avoid places where you have come to believe your somatic OCD began. You may have thoughts like, “That park is where I started being hyperfocused on my breath. I remember it so clearly. I’ll never go to that park again.”

The most effective treatment for somatic OCD

Exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy

The best course of treatment for somatic OCD is exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy. ERP is a specialized form of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that was created to treat all types of OCD.

As part of ERP therapy, you will track your obsessions and compulsions and make a list of how distressing each thought is—and then create an exposure hierarchy of the ERP exercises you’ll work on. You’ll work with your therapist to gradually expose you to your fears (exposure), while teaching you to resist doing compulsions (response prevention) to relieve anxiety.

For example, you may start with a less distressing exposure, like noticing your breath for a short time without checking or counting, and slowly work up to more challenging exposures, such as resisting the urge to monitor your blink rate or swallowing process. By repeatedly facing these fears without resorting to compulsions, the distress associated with them will lessen over time, allowing you to regain control and reduce the intensity of the obsessive thoughts.

ERP examples for somatic OCD

If you’ve ever tried not thinking about something, you know how difficult it is to stop your mind from focusing on something specific intentionally. ERP therapy takes the opposite approach. Instead of trying to make yourself stop your obsessive thoughts, you welcome them.

Here are some examples of ERP for somatic OCD:

Obsession: You worry that you’re blinking too much or too little, and that something might be wrong with your eyes or vision.

Compulsion: You may check your blink rate, avoid blinking for long periods of time, or ask others if you’re blinking “correctly.”

ERP exercise: Start by purposefully blinking frequently for a short period of time and gradually increase the time you go without checking or monitoring your blink rate. As you resist the urge to check or control the blinking, you’ll gradually learn that nothing bad happens when you don’t monitor it.

Obsession: You fear that you might stop breathing or not be able to control your breathing.

Compulsion: You may monitor your breath, take deep breaths to “make sure” you’re breathing properly, or avoid certain activities that might trigger anxiety about breathing.

ERP exercise: Start by focusing on your breathing, but don’t try to control it or check if it’s normal. Set a timer and, over time, extend the period where you allow your breathing to happen naturally without checking. Gradually expose yourself to situations where you’re more likely to notice your breathing, like exercising, without trying to regulate it.

Bottom line

If you’re experiencing obsessions about your bodily sensations or functions (like breathing, blinking, swallowing), it could be a sign of somatic OCD.

Together with an ERP therapist, you can learn how to experience automatic bodily functions (or sensations) without having to respond with a compulsion. Over time, you’ll learn how to perform regular bodily processes without becoming completely overwhelmed by them.

Key Takeaways

- Somatic OCD is a subtype of obsessive-compulsive disorder that’s characterized by excessive focus on automatic bodily sensations and functions like breathing, blinking, swallowing, heart rate, etc.

- In response to obsessions, someone with somatic OCD performs compulsions which may include distraction, excessive research, mental review, reassurance seeking, or avoidance.

- Somatic OCD can be treated with exposure and response prevention (ERP), a specialized form of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).