Disordered thinking. Hallucinations. Delusions. These are just some of the symptoms of psychosis which can be best described as an inability to determine what’s real and what isn’t.

Psychosis isn’t a specific disorder but rather a symptom or feature associated with several different mental health conditions. It’s estimated that while 1.5 to 3.5% of people will meet the criteria of a psychotic disorder in their lifetime, many more will experience psychotic symptoms at some point.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), on the other hand, is a complex mental health condition characterized by intrusive thoughts and repetitive behaviors that can significantly impact daily life. While OCD and psychosis are quite distinct from one another, they do share some potential connections and fascinating relationships that we’ll explore.

What is OCD?

Before we launch into how OCD and psychosis are related, let’s first get to grips with what each term means and the impact they can make in people’s lives.

OCD is a serious but widely misunderstood mental health condition that affects around 1 in 40 people characterized by distressing intrusive thoughts, images, and urges—known as obsessions—and compulsions, which are thoughts or acts intended to neutralize the distress caused by them. You might hear people casually claim to “be a little OCD” from time to time, but statements like these belie the fact that to be properly diagnosed with the condition, a person has to meet several criteria:

- Recurrent thoughts, images, or urges that cause distress

- Repetitive behaviors or mental rituals intended to alleviate that anxiety

- The obsessions or compulsions are time-consuming (occupying over 1 hour per day), cause significant distress, or interfere with daily activities like work, school, and relationships

The symptoms of OCD can range from mild to debilitating, but, as you can see, even the mildest case of OCD involves a meaningful amount of distress and eats up a significant portion of the day.

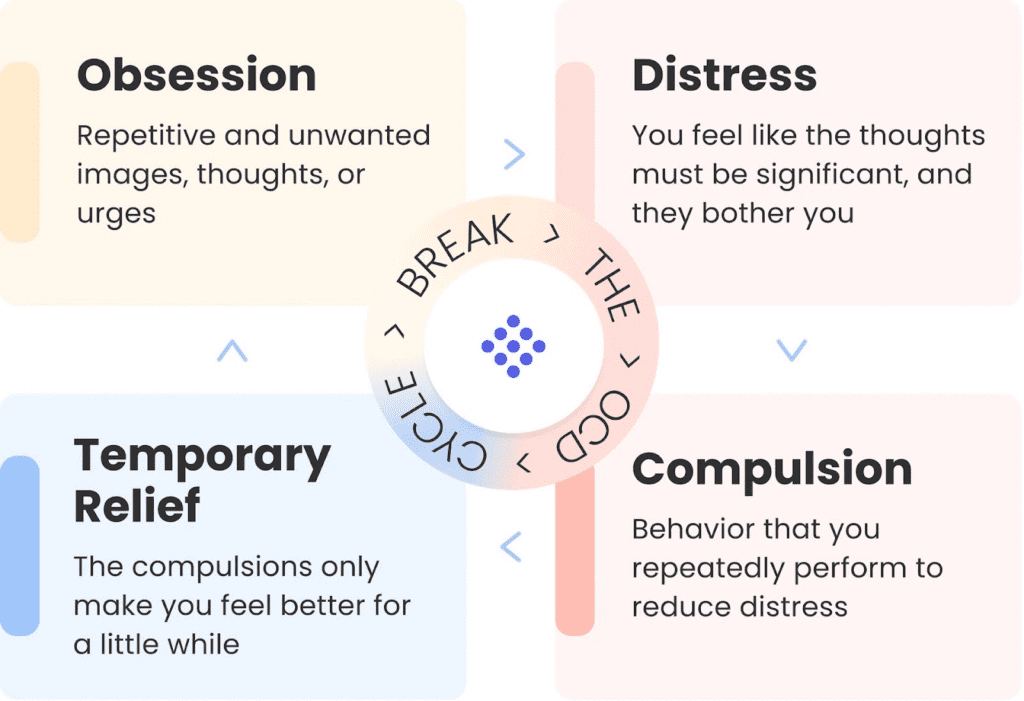

What’s more, OCD tends to get worse when left untreated, as obsessions and compulsions combine to form a vicious cycle:

- Obsession: At the cycle’s core lies a specific thought, image, situation, or feeling that triggers anxiety or distress. Examples include fears of contamination, doubts about safety, or concerns about harm to oneself or others.

- Distress: The presence of obsessions leads to the emergence of intense anxiety or fear, intensifying the grip of OCD on the individual’s mind.

- Compulsion: To alleviate the distressing level of anxiety, people engage in compulsive behaviors or mental rituals. Common examples include excessive hand washing, checking, counting, or seeking reassurance.

- Temporary relief: The performance of compulsive behaviors provides short-lived relief, reinforcing the belief that these actions are necessary to avert harm or alleviate anxiety, and causing the cycle to repeat time and again.

This cycle creates far-reaching, compounding effects. At work, it can cause reduced productivity, difficulty concentrating, and impaired decision-making. Socially, OCD may cause individuals to avoid certain situations or valued activities due to anxiety or compulsive avoidance of potential triggers. Relationships can also be strained, as partners or family members struggle to understand and cope with repetitive behaviors, demands for reassurance, or the constant need for accommodation.

Psychosis explained

Psychosis is a complex and distressing mental state that affects a person’s thoughts, perceptions, and behaviors. When experiencing psychosis, individuals may have hallucinations, which are seeing or hearing things that aren’t actually there, or delusions, which are strongly held beliefs that are not based on reality.

Again, psychosis is not a disorder but rather a collection of symptoms associated with several mental disorders, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and certain forms of bipolar disorder.

Schizophrenia: Schizophrenia is perhaps the most well-known disorder linked to psychosis. It is a chronic condition that affects a person’s thinking, emotions, and behaviors.

Schizoaffective disorder: Schizoaffective disorder combines symptoms of both schizophrenia and mood disorders like depression or bipolar disorder, resulting in a complex presentation of symptoms.

Bipolar disorder: Bipolar disorder, specifically during manic or severe depressive episodes, can also trigger psychotic symptoms. These episodes involve extreme shifts in mood, energy levels, and activity. During manic episodes, individuals may experience grandiose delusions or hallucinations, while severe depressive episodes can lead to psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations, as well as intense feelings of guilt or worthlessness.

Psychosis can also occur due to drug use, extreme stress, or certain medical conditions. Regardless of the cause, psychosis can be intensely frightening and disruptive, both to the person experiencing it and the people around them.

Psychosis and OCD

While studies have shown that psychotic symptoms like hallucinations, delusions, and disordered thinking are more common in people with OCD than in the general population, the answer to the question posed at the top of this page is no: OCD cannot cause psychosis. That’s not to say that OCD and psychosis don’t share some things in common, however.

“A common overlap between OCD and psychosis is their association with anxiety,” says Aaron Hensley, MSW, LCSW, a therapist at NOCD. “But there’s a major distinction there. Psychosis is going to look more like paranoia—a fear of being watched or someone coming to get them. OCD, on the other hand, is based on the fear of a bad thing happening, with compulsions being enacted in an attempt to prevent it from taking place.”

Hensley adds that, with OCD, the intrusive thoughts are ego-dystonic, meaning that they contradict the sufferer’s core values and beliefs. Hallucinations, delusions, and other symptoms of psychosis, by contrast, don’t necessarily relate to a person’s identity, beliefs, or intentions at all. He also notes that while OCD doesn’t cause psychosis, people with OCD can have obsessive fears about developing psychotic symptoms—often with debilitating effects.

“I once worked with a gentleman who was a well-established medical doctor,” he says. “His OCD was based on his fear of having a panic attack and going into psychosis. He was afraid that if he had a panic attack, it would somehow cause him to snap, and he would become psychotic. He became fixated on the idea that a change in his vision would herald a panic attack and, subsequently, a psychotic episode. His compulsion was to take his sunglasses on and off—hundreds of times—to check that his vision wasn’t altered. In his mind, this checking behavior was to relieve his anxiety about becoming psychotic.”

Hensley explains that a fear of psychosis is more common among people with obsessions around panic attacks or a very strong anxiety response. He adds that if someone has little to no awareness of their OCD, they’re far less likely to view their obsessive thoughts or compulsions as problematic or unreasonable, and may actually confuse their experience with psychosis.

“From their perspective, it can seem as though they’ve lost touch with reality, which is, in essence, what a psychotic episode is,” says Hensley. “That’s why the education piece of exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP) is so important.”

Exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP)

Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) therapy is highly effective in treating OCD symptoms—including those that could be mistaken for psychotic episodes—and has been shown to lead to significant benefits in life, even beyond OCD symptoms.

ERP involves gradually exposing people to situations that trigger obsessive thoughts or fears (exposures) while preventing them from engaging in compulsive or avoidant behaviors for short-term relief (response prevention). In doing so, they develop other ways of coping with distress that reduce the power of their obsessive fears, rather than reinforcing them and strengthening them over time.

“If someone has OCD and their insight is so low that they’re having nearly delusional beliefs, ERP is still our best approach to treatment,” says Hensley. “The only change would be an emphasis on the education part, because we wanna make sure that we’re giving them the most insight about their actual condition before we start the exposures. Without increasing that level of awareness, we could risk making things worse by causing them to feel that they’re actually having a psychotic episode.” It may also be important for someone with these themes of OCD to consult a psychiatrist to see if medication may help in treatment.

“If I’m working with someone whose OCD centers around a fear of becoming psychotic or developing psychosis, ERP is also our best bet! We would do it the same way we do it with every other form of OCD—exposure to their triggers, then developing the tools they need to not respond with compulsive behavior. In my example from earlier, we developed exposures involving things that would trigger his worries about becoming psychotic. We slowly but surely worked up to him driving with his glasses on the whole time, not taking them off to check if his vision had changed and that a psychotic episode was imminent.”

With ERP, you’ll learn to tolerate the distress associated with uncertainty and develop the skills you need to manage intrusive thoughts and fears in the long term. This will allow you to live life as you want—according to your knowledge, values, and decisions—rather than being ruled by fear of psychosis and compulsive behaviors done to avoid it at all costs. Moreover, improvements can often be seen just a few weeks after beginning treatment.

You can get on the road to recovery today

If you think you might have OCD and are interested in learning how it’s treated with ERP, I encourage you to learn more about NOCD’s evidence-based approach to treating OCD and related conditions.

All of our therapists specialize in OCD and receive ERP-specific training. You can also get 24/7 access to personalized self-management tools built by people who have been through OCD and successfully recovered.