Though it didn’t make it into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) until 1980, German psychiatrist Carl Westphal first described Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) way back in 1877. To put that in perspective, Germany had only been a country for six years by that point.

So it’s pretty safe to say that OCD has been categorized as a mental illness for quite a long time.

It should be noted that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental DIsorders (DSM) categorizes many conditions as mental illnesses. There is ongoing debate these days about specific terms, and some propose using other terms like “mental health conditions” rather than “illness.” Since we are discussing questions of categorization, for the purposes of this article we will use the term “mental illness,” as that is still the official term.

Despite its official status as a mental illness, OCD’s symptoms, definition, and seriousness continue to be misunderstood. Read on to learn about what constitutes a mental illness, why OCD fits the bill, and what might contribute to the enduring misconceptions about OCD.

What is mental illness?

To get a handle on what constitutes a mental illness, let’s first define mental health. The World Health Organization (WHO) provides a simple definition: a state of well-being where an individual can realize their potential, cope with the everyday stresses of life, work productively, and contribute to their community.

Mental illness, then, can refer to any condition that interferes with mental health by impacting a person’s emotions, thinking, or behavior.

Understanding Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

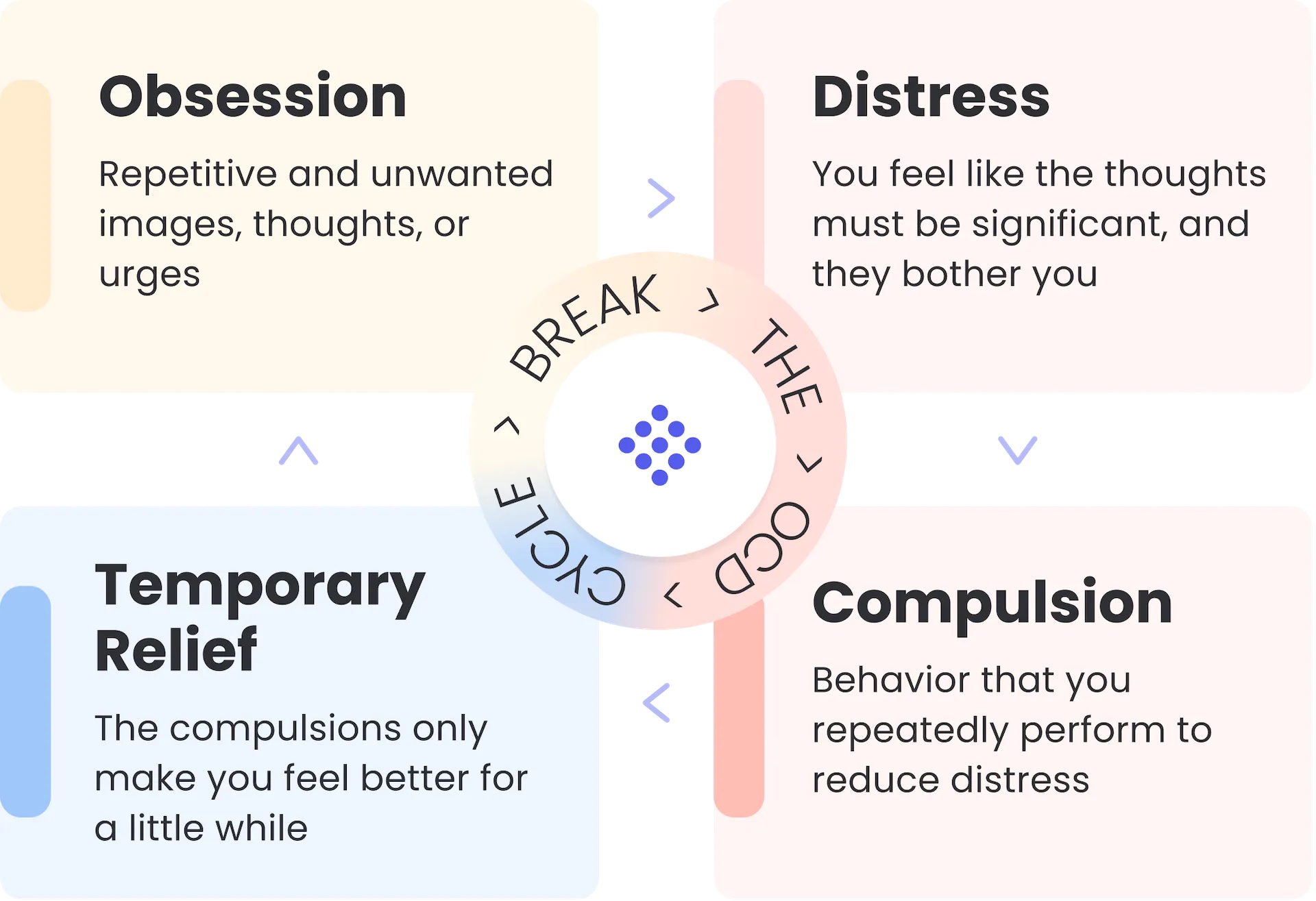

OCD is a disorder that affects about 1-2% of the population. It’s characterized by unwanted, intrusive thoughts, urges, or images that cause distress (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions) that individuals feel compelled to perform in response to these obsessions.

The compulsions are intended to reduce distress or prevent a feared outcome associated with the obsession. The relief these compulsions bring, however, is only temporary and actually serves to perpetuate a vicious cycle that tends to get worse when people go without treatment.

Over time, the OCD cycle can become more intense and time-consuming, leading to significant interference in a person’s daily life. For example, a person with OCD may spend hours each day engaging in rituals or avoiding situations that trigger their obsessions. This can lead to social isolation, impaired work or academic performance, and difficulty maintaining relationships.

OCD symptoms can range from mild to completely debilitating, and it can also take any number of forms, called themes or subtypes. Here are just a few common examples, among innumerable possible themes:

- Contamination OCD: Excessive fear of contamination or germs, leading to compulsive cleaning, avoidance of certain objects or places, and heightened hygiene rituals.

- Checking OCD: Persistent need to repeatedly check things (e.g., locks, appliances, or personal belongings) due to intense anxiety about potential harm or mistakes.

- Order and Symmetry OCD: Obsession with symmetry, order, and exactness, resulting in compulsive behaviors like arranging objects in a particular way or repeating tasks until they feel perfect.

- Just-Right OCD: Uncomfortable feeling that things are not “just right” or incomplete, leading to repetitive actions or rituals until a sense of completion or satisfaction is achieved.

- Harm OCD: Persistent and intrusive thoughts or fears of harming oneself or others, accompanied by compulsive behaviors to prevent harm.

- Religious or Moral OCD (Scrupulosity): Obsessions related to religion, morality, or ethics, often involving excessive guilt, fear of sinning, or doubt about moral correctness, leading to rituals or excessive religious practices done out of fear.

- Relationship OCD: Obsessive doubts, fears, or uncertainties about romantic relationships, leading to repetitive reassurance-seeking, analyzing behaviors, and seeking proof of love or compatibility.

The first few subtypes on this list are most over-represented—though still often mischaracterized—in the media. As a result, they are most commonly associated with OCD among the general population.

“The distress that OCD causes is really downplayed in media portrayals,” explains Jason Gibbs, Ph.D., a therapist who specializes in treating OCD. “Contamination, checking, symmetry, and order OCD, can all generate debilitating levels of anxiety and distress, but if you’re having intrusive thoughts about molesting a child or stabbing someone, it can bring shame and guilt that the media doesn’t touch and, as a result, the general public doesn’t know about.”

Gibbs adds that the lighthearted treatment of the subject in popular culture could lead the average person to see OCD as a personality quirk and not the potentially debilitating mental illness it really is. These caricatures and stereotypes are just one reason OCD isn’t often thought of the way PTSD is, for example.

“Another thing the media fails to portray is why this illness appears in the first place,” Gibbs elaborates. “While the exact cause of OCD is unknown, research suggests that a combination of genetic, neurological, and environmental factors may bring it on. Some studies have even shown that people with OCD have differences in brain structure and function, particularly in the parts of the brain that regulate mood, behavior, and cognition.

“I think an important thing to understand about OCD is that the obsessions are generally just extensions of normal intrusive thoughts that everyone has,” says Gibbs. “Although they may not want to admit it, most people have random, fleeting thoughts about hurting someone, for instance. It just doesn’t cause them the same distress.”

“Most people with OCD are really good people. They just have their brain wired in such a way that they can’t get these thoughts, these images, these urges out of their head. However, they’re no more likely to act on them than someone without OCD. In fact, it’s probably less likely that someone with OCD would ever act on an intrusive thought or urge than someone without it. They would go to any length to avoid it.”

OCD as a mental illness

As we’ve learned, OCD classification as a mental illness has been well-supported for a long time.

Its inclusion in the third, fourth, and current version of the DSM (DSM-5) underscores the fact that OCD is a recognized mental health condition that requires specialized treatment.

“The average time it takes a person to get help for their OCD is between 14 and 17 years,” explains Gibbs. “That’s a lot of time to not have control of your life. There’s a host of reasons why this particular disorder goes untreated for so long, but the misunderstanding and stigma around it can be a big part of that delay.”

Recognizing OCD as a mental illness can help reduce stigma and increase awareness of the condition. And even more importantly, accurate education about what OCD is and how to recognize it can allow people to actually improve their lives and recover from OCD’s impact.

“I have a lot of intelligent people coming into treatment,” says Gibbs. “By the time they come to me, they’ve often done their research and realized that they likely have the disorder and that this isn’t some random quirk that’s going on with them. From there, we can make a diagnosis and begin the most effective therapy for this illness. It’s called exposure and response prevention therapy, or ERP.”

The gold standard treatment for OCD: Exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP)

ERP is a form of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) specifically designed for OCD around 60 years ago. It involves being exposed to anxiety-provoking situations or thoughts (exposures) while actively resisting the urge to engage in your usual compulsive behaviors or rituals (response prevention).

Someone undergoing ERP will work collaboratively with a therapist who, like Dr. Gibbs, specializes in treating OCD. Together, you’ll identify the specific obsessions, triggers, and compulsions that keep the OCD cycle going. The therapist will help you create a hierarchy of feared situations or thoughts, starting with those that cause mild anxiety and progressing to more challenging ones. This hierarchy serves as a guide for gradually exposing you to your fears.

From here, you’ll engage in exposure exercises. This is when you intentionally confront your feared situations or thoughts without engaging in compulsions or rituals. These exposures can be done both in therapy sessions and as homework assignments. During exposure exercises, you’ll be actively encouraged to resist the urge to engage in your typical compulsive behaviors. By doing so, you’ll learn that anxiety naturally diminishes over time without performing rituals. The goal is to habituate to the anxiety and develop new, healthier responses to triggers.

Getting help

If you think you might have OCD and are interested in learning how it’s treated with ERP, schedule a free 15-minute call with the NOCD Care team to learn more about how we can help you.

All of our therapists specialize in OCD and receive ERP-specific training. You can also get 24/7 access to personalized self-management tools built by people who have been through OCD and successfully recovered.