My first OCD tantrum occurred when I was perhaps 7 or 8 years old, except back then it didn’t have a label yet. I had spent a lot of time and care folding all my blankets from corner to corner, side to side. It was all aligned just right and perfectly and placed just right at the bottom end of my bed at night. My father came into the room to check on us kids and proceeded to unfold all of my blankets and covered me with all of them. That might have seemingly been a caring thing to do, but for me, it was tormenting. I can still remember it like it was yesterday. I recall how I repeatedly slammed my fist and legs onto my bed in an anxiety-fueled rage.

Just-right and perfectionism OCD themes played out in various ways in my younger years. If I made a mistake when I was handwriting something, I’d throw out the paper and start all over again. I struggled to use the whiteout function on typewriters because you could still see the imprint of the letters I tried to whiteout or delete, as they say, in computer language. By this time I had learned that I shouldn’t waste paper.

This was the first of many should-nots that would visit my life.

I needed to conserve resources, not be wasteful. I felt that I had to use the same pen and pencil until they were completely used up before I would allow myself the luxury of using a fresh one. I put things in certain places, arranged things in a specific way, and checked and rechecked that I had certain items in my backpack. I had a routine way of doing things. As a child, I grew up with the habit of changing from my outside clothes into my inside clothes. I took care to ensure that I placed dirty things in specific places in my home. I would mentally review or replay things in my mind over and over again. Did I say something that made me look stupid? What if I said or did that one thing differently that would have made the situation turn out the way I would have wanted it to? Thoughts like these would run rampant in my mind. During bedtime, I’d ruminate for hours about these thoughts. I worried about things that had not yet come to pass. I learned that silence can be a ruminator’s worst nightmare.

It became debilitating

Contamination OCD was more noticeable the first time I lived away from home and shared living space and bathroom with people I had just met. I adjusted by doing things like wearing flip-flops in the shower, avoiding touching the shower walls, and avoiding touching doorknobs directly with my hands. As I became older and moved into my own apartment there were a lot of rules if you were permitted to visit my place. Some of these rules consisted of where to put your contaminated bag(s), or where you could sit when wearing your “dirty” outside clothes. After every visit, I would decontaminate my apartment, it was time-consuming and exhausting.

There were so many rules that needed to be followed.

During my college years, I struggled with my perfectionism, still, it didn’t have a label yet. I attended school full-time, worked a part-time job on campus, chartered a sorority at my University, was a dedicated member and officer of social clubs, and had a dating life. All of this while being the dutiful daughter at home. I can remember crying in front of my professor when I got my first “C”. Depression started to creep up on me, but again, I didn’t have a label for it yet.

I recall the tears of my work administrator when she had to fire me because of my frequent lateness and call-outs. Due to these additional stressors, I took a leave of absence from college. I experienced the first debilitating episode in my life where I stayed in bed all day, hygiene went out the window, and I became more withdrawn, isolated, irritable, and depressed. I was extremely lost and so confused. I felt that I was such a complete and utter failure.

I was exhausted and depleted.

I grew up in a culture where you were supposed to “save face” and where you didn’t go outside of the family to ask for help. I also didn’t know how to ask for help within my own family. Living with perfectionism, I could not admit when I made a mistake or when I struggled. I compared myself to my peers and even more crucially, to my siblings. My thoughts were about my failures. Other times, I just avoided my thoughts in maladaptive ways.

In Chinese culture, I wasn’t good enough as an American Born Chinese (ABC). My values were torn between that identity of being Chinese versus American. If I choose myself, I’m selfish and more American. There was no such thing called self-care or relaxation. I just continued to struggle alone with the yet-to-be-labeled OCD that had latched on to so much. This was further compounded by the depression that seemed to envelop my spirit and soul.

In service to others and myself

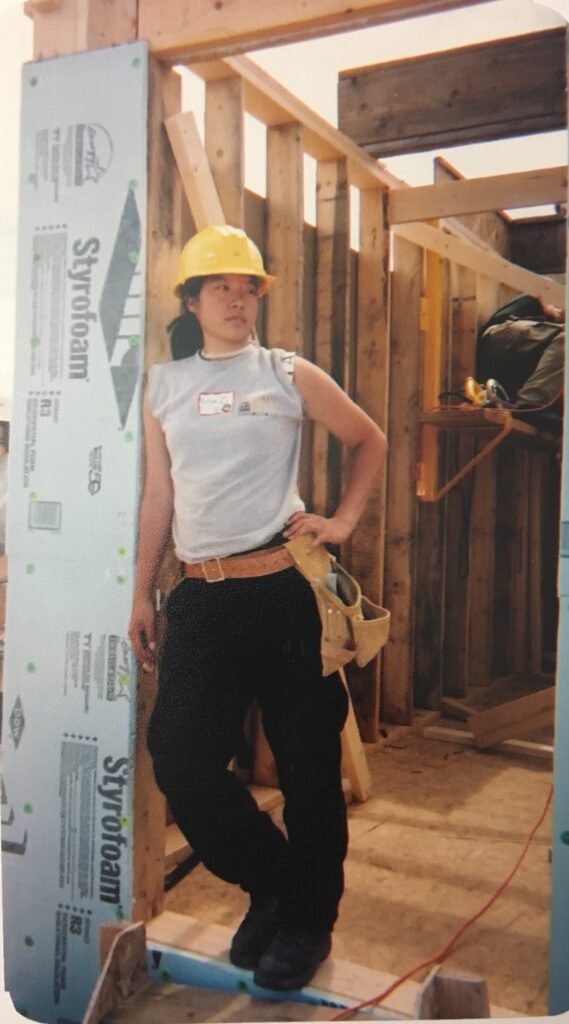

I made a choice and applied to AmeriCorps’ NCCC volunteer program. As a New Yorker living in the Midwest, I joined teams of people from across the U.S. who had a shared goal and a common spirit. For the first time, I didn’t feel the weight of high expectations that I placed on myself and wasn’t influenced by others around me. I just needed to discover myself with less anxiety, guilt, shame, and stress. Decades later, I can still recall with clarity, the clear skies in the Indianapolis YMCA campground, the brilliant stars, surrounded by endless trees, and the peace I felt back then. As a child, I didn’t learn how to relax, take a step back, take a moment to breathe or give myself credit for anything. All of those things were seen as a privilege. That one choice I made become a pivotal moment in my life. The choice to take that service year. The choice to make finding myself a priority. After my service year, I returned home to finish and obtain my college degree. It would take me several years and changing majors but I got there.

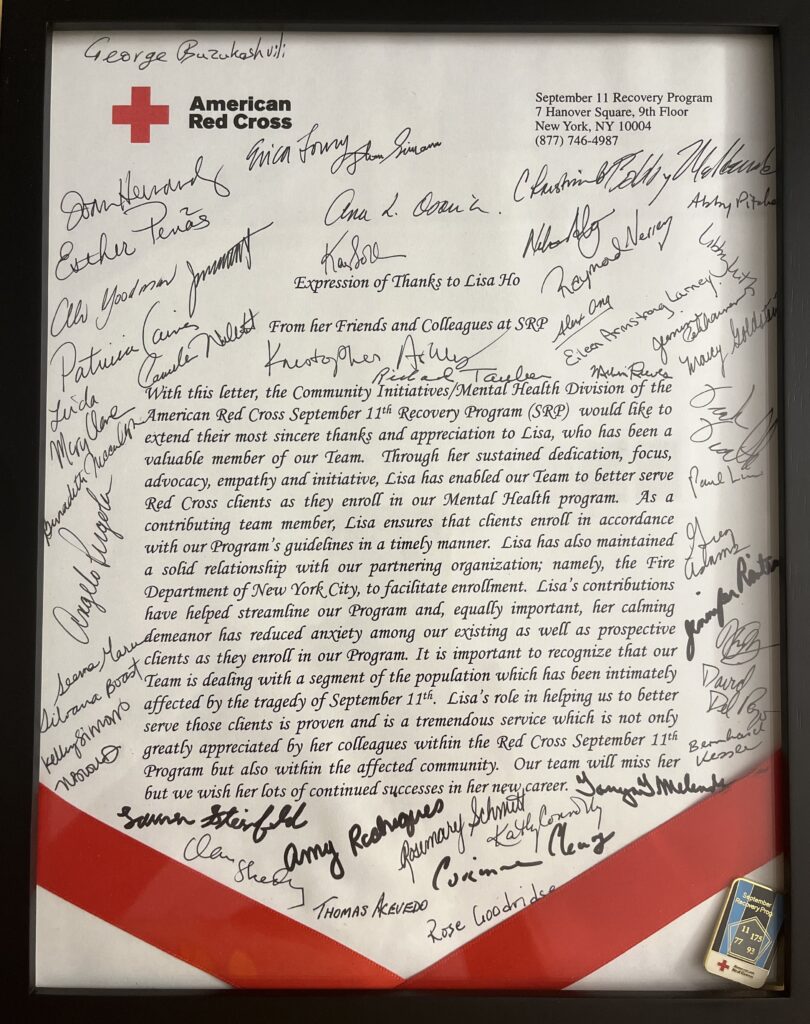

I worked for the American Red Cross 9/11 Mental Health program as a caseworker. During this time, I tried to explain to my parents what my job entailed. Before translation devices/apps, I did not have the words in Chinese to say “mental health”, instead all I could refer to was “sick in the head” or “sick in the heart”. This was the only way they could maybe understand a bit. If I couldn’t tell them about my job, how could I tell them about my own personal experience? How could they possibly understand?

During this time, I found the courage to be vulnerable and sought help from a mental health professional. I was treated for anxiety and depression. I learned about vicarious trauma and burnout. I learned what it meant to take care of myself. I started to learn about my fears. A few years later in California, while in my social work master’s program, I returned to psychotherapy. I started to learn to let go and leaned more toward acceptance. I recall bringing up OCD to my then-therapist who responded only by recognition of some “mild traits” and the topic was dismissed. This was not the fault of the therapist. I recognize now that at the time, I didn’t have enough insight to share my mental compulsions. A therapist needs specialized training to accurately diagnose and treat OCD.

In the past few years, as Covid was reaching the U.S. shores, one workplace incident would result in my taking a leave of absence from my job due to post-traumatic stress. I am still working through parts of my story here so in simplest terms:

(Leave of absence from job + Perfectionism OCD) + (Covid + Contamination OCD) + Depression + PTS = Debilitating Episode #2

Disastrously, during this time the term “Kung Flu” spread across the United States. Asian hate became prevalent again here in the U.S. Can you imagine what it might have been like for someone like me? Despite my resiliency, my tools, and my support system – I went back on the struggle bus.

To be worthy of you, I must be worthy of me

I have worked within the mental health field for 20-plus years. I have evolved in how my perfectionism has impacted my life. I have explored ways in which it has been a strength versus a detriment in my service to others as a case worker, as a supervisor, as a director, and as a therapist. I have grown into how I practice self-care, knowing that if I do not take time for myself, I am not much good to anyone else. I have been in and out of therapy for 20+ years and received psychodynamic therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and ketamine-assisted psychotherapy. I have sought out training for certifications in mindfulness and trauma-informed care practices. I have never received exposure and response prevention (ERP) treatment from a mental health professional. It is only now that I do my own ERP work.

As a trained ERP therapist with NOCD, I help others who are experiencing areas where I once struggled. I understand what it means to activate out of depression, confront your fears, sit with distress, learning not to go over the threshold into panic, set healthier boundaries, and to more effectively practice self-care.

I still end up on the struggle bus from time to time, but it’s for a shorter ride each time. Mental wellness is a lifelong journey. It is through my education, training, work, and life experiences that I have come to rediscover myself, and be my authentic self, holding true to my values in all areas of my life with balance and acceptance.

To all NOCD members I work or have worked with – thank you for your trust in me, in the ERP journey, and in your faith in NOCD and the NOCD community. It’s an honor to be an ERP therapist. It provides me the opportunity to challenge myself to be triggered all day every day in the work we do together. It’s a pleasure to heal together. Proud and privileged to expand the web of goodness.