Superstitions. Counting numbers. Listening to one song hundreds of times a day. Every human on the planet has quirks, but I recognized from a young age that mine started earlier than other people I knew. I also acknowledged that they were quite intense, and seemed a little more peculiar. What I didn’t know until much later was that obsessive-compulsive disorder differentiated my idiosyncrasies from those of a typical person. Mix that with a lack of professional mental healthcare and having a universally known last name due to my father’s decades-long fame, and it created a recipe for disaster. I’ve emerged from the ethers stronger than I might have been had I not battled OCD. And though not entirely unscathed, I am still learning, healing, and tackling the disorder with vigor.

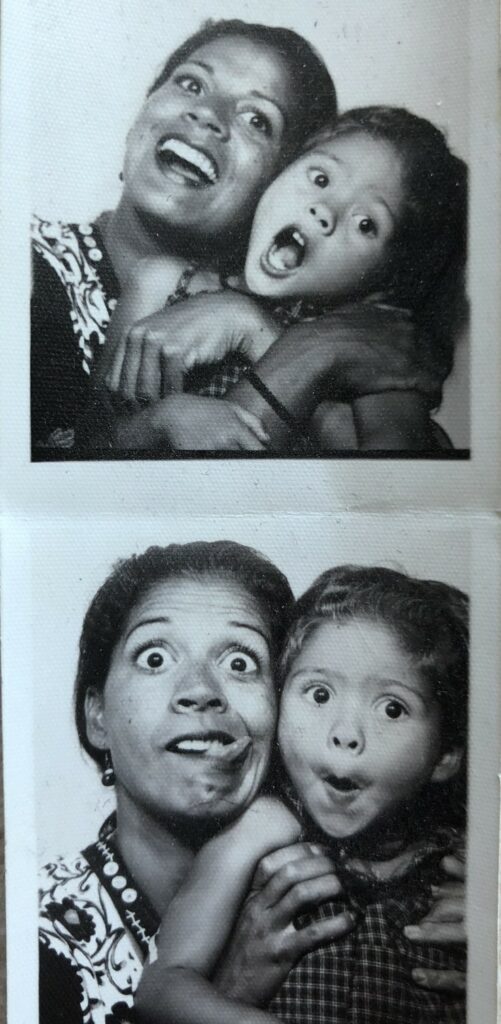

My mom often jotted down her thoughts about my cuteness and quirkiness in my baby journal. She documented how I, at age two, would throw tantrums when my layered shirt sleeves didn’t line up perfectly. Of course, I don’t remember those exact moments, but I understand my toddler-aged reasoning. Twenty-something years later, I’ll still want to bawl my eyes out if something doesn’t feel “just right.” This applies to many scenarios: the manner in which I clean something unsanitary, picking my face, how I rotate my left shoulder while seated or walking, or adjusting my knee so that it pops a certain number of times. Oh, and obsessively purchasing things that I believe I need at that moment. If I don’t find that “just right” feeling, a sense of unease and panic builds up and pulses through my veins, leading me into what feels like is going to be a permanently petrified state of mind.

My mind, like many others with OCD, works like a sticky fly trap: it catches every little thing that floats by, even when (especially when) it’s not beneficial to my mental well-being. This means that every insult from a classmate growing up, every melancholy tale I accidentally read, and every scary movie I sneak-watched as a preteen has clung to the walls of my brain until this very day. But what makes the disorder so unbearable at times are cycles of severe intrusive thoughts that bring up those memories, presenting themselves as words, phrases, or images that play in my head.

My mind, like many others with OCD, works like a sticky fly trap: it catches every little thing that floats by…

The severity of these thoughts depends on my mental state. If I’m happy: zilch. If I’m neutral, I can sometimes feel like I’m on the verge of angst—a wave of nerves can hit at any time, but I’m balanced enough to keep thinking forward. However, if I am feeling depressed, that’s when it’s like a ticking time bomb. Obsessions arise, which lead to intrusive thoughts that, in a nutshell, tell me everything around me is unsafe, sinister, or immoral. After that, I get anxiety so severe that it shakes me to the core—literally. The anxiety manifests by presenting itself physically in many parts of my body. Chest tightness and pressure, nerve pain, and muscle tension can last for weeks. The bottoms of my feet burn as if I’m walking barefoot on the Vegas Strip in summer. Tingling sensations overtake my forehead and scalp as if I were being tickled by a feather.

It feels like I don’t have control over my mind, and that my body isn’t a safe space to live in.

Before I knew that my symptoms were indicative of OCD, I had my other theories, like the possibility of having Tourette Syndrome. I’d heard of the nervous system disorder, and how people with it can say unwanted words and phrases, or make unwanted sounds and movements. I related to the physical tics, but instead of saying things out loud, my undesired words and phrases purely popped into my head. Another hypothesis throughout my early twenties was that I could simply have severe anxiety. But I soon realized that my experience didn’t line up with doctors’ or Google’s descriptions of anxiety. I didn’t dare share the details of what I was experiencing with other people for fear that I would be looked at as completely unhinged. Because I didn’t seek professional help, I never got any diagnoses that could have benefited me and validated my experience.

My self-developed techniques to combat distressing thoughts and images have historically been to replace, replace, replace. I thought that if I quickly thought of a happy word, an image of a meadow, or the most random phrase I could possibly come up with, it would trick my mind into counteracting the intrusive thought. What started as a mantra of the words “love and light” in my teens, turned into much more bizarre techniques in my twenties. Pretty soon, I was saying phrases such as “ketchup and mustard” in my head upwards of 100 times a day. When that wasn’t enough to help, I turned to everything physical: I tried all the different diets, natural supplements, meditation, acupuncture, lymphatic drainage massage, infrared saunas, float therapy, and even a colonic. I went to more than ten doctors in the span of two years and had every blood test in the book. I did weekly psychotherapy with a psychiatrist, but no matter how many events from my unconventional childhood she analyzed, I did not improve.

I’ve often wondered what the worst point of my OCD has been. Was it when I couldn’t look at the leftover marinara sauce on a plate because the color red suddenly terrified me? Or maybe it was the time I drove back and forth on a Hawaiian highway in my grandpa’s beater car to make sure that what was certainly just a gust of wind wasn’t actually the feeling that I had run over a pedestrian. The truth is, it doesn’t matter what the low point of my disorder was— ruminating will never take away what I’ve gone through.

In the past year, I have done more valuable work on myself than ever before, finally breaking the cycle I was stuck inside for over a decade.

My journey has been full of twists and turns and far from perfect. New obsessive thoughts come and go and will most likely continue. Just the other day, I had a thought that if my boyfriend didn’t say, “Bless you” after I sneezed, something bad was going to happen. But that is to be expected for someone with OCD, and acquiescing to discomfort is what helps me most on a day-to-day basis. Thoughts now pass through my mind, in one side and out the other, as quickly as they appear, and that’s extremely comforting.

In 2023, I’ve now stopped going to doctors seeking physical explanations of what is a very mental thing. I have a fantastic relationship with my current psychiatrist, who has given me the information and courage I needed in order to start medication which has been vital to my improvement. The next step in my process will be to begin Exposure and Response Prevention therapy (ERP,) something that’s been a long time coming. I exercise, even though I’ve never loved to because I know it makes my brain and body genuinely feel good. I surround myself with the greatest support system I can imagine, and am my most authentic self around my friends, family, and even people I meet on the street. I can laugh about my idiosyncrasies. This may be a lifelong journey, but if OCD wants to try to drag me along, I’ll at least try to pick myself up and run with it.