In an effort to bring attention away from misinformed memes and joke posts toward those rare good things being made about OCD, we’re starting a new series that will highlight movies, books, podcasts, and anything else.

UNSTUCK: An OCD Kids Movie (Documentary, 2017, 22min)

Kelly Anderson (Director), Chris Baier (Producer)

Country: USA

Language: English

Rating: Not Rated

A journey with kids and teens who really have OCD

There’s so much nonsense across the internet about obsessive-compulsive disorder– from social media stars using misinformed depictions to get attention to countless ridiculous listicles– that it’s hard not to notice when something sensical arrives to provide new insights into the lived experiences of people with OCD.

In the case of the documentary film UNSTUCK: An OCD Kids Movie, those people are, of course, kids. An estimated 1 in 200 children has OCD in the United States, and the brief but moving UNSTUCK puts six of them in front of a camera to take you through their journey, from the extremely confusing first symptoms through their eventual diagnosis and treatment with Exposure and Response Prevention.

The movie begins with Vanessa, who stands out as especially self-aware even in this group of six young people who never miss a beat. The voice of director Kelly Anderson prompts Vanessa to introduce herself. Vanessa says she’s ten years old and lives in Brooklyn, New York. Then, pausing for a second and leaning back in her chair, Vanessa says, “And I have OCD.” It’s the first sign of many that these kids have come to accept their obsessive-compulsive symptoms as part of their daily reality.

But how did that reality look before those symptoms were recognized as OCD? The film, adopting its pattern of cutting between brief interviews with each of its six stars, gives them a chance to tell us. Holden’s obsessions had him convinced he would suddenly become a bodybuilder if he interacted with anything related to bodybuilding or strength. The avoidance spiraled: he couldn’t look at the Hulk, which meant he couldn’t wear the color green; if he saw a strong character in a cartoon he would have to blink or breathe in a certain way and then turn off the TV, which would be contaminated from that point on. As Holden tells it, “And then I couldn’t use any of the electronics. So I literally just sat around all day.”

The whole family gets involved

Some of the most compelling moments in this documentary are when the kids talk about how their symptoms gradually roped in their entire family. Jake tells us his parents would try to discourage his rituals by doing his chores, hiding things from him, and otherwise enabling him to avoid the emotional distress that would normally lead to compulsions. Jake says, “I felt really bad for them, because they were basically stuck in the rituals with me.”

Sarah, who remembers feeling like her conscience was telling her that things had to be just right, would ask her parents to say or do things repeatedly until they felt perfect. She reveals another tragedy of being a young person with OCD: “And at that time my parents didn’t know it was OCD, so they thought it was just me being disobedient. And so, yeah, it was hard.”

Most powerful are the scenes when other family members are brought on camera. In one of these, Vanessa and her sister Charlotte sit across from one another. Charlotte looks at her intently, and Vanessa asks, “What do you think the hardest thing was?”

Charlotte replies, “Well, at first the hardest thing was you didn’t tell me about it. I didn’t even know something existed called OCD. It was also very hard when you were kind of a little afraid of me.” She explains that her frequent stomach aches made Vanessa avoid her out of fear she might get sick. Then she continues, “It’s kind of like, what did I do to make her feel like this?”

Demonstrating as always an impressive amount of maturity and self-awareness, these kids keep getting straight to the point about what’s so difficult about mental health conditions, whether you’re the person who has one or someone who cares a lot about them. The camera lingers on them just long enough after each statement, but keeps us moving quickly through the six stories until the film’s twenty-two minutes have suddenly slipped away.

Getting better

Their first forays into therapy don’t go too well. Ariel, whose mom surprised her by taking her to see a psychologist one night, says, “I was just really upset from my mom taking me there. I didn’t want to talk to her about anything. I didn’t want her to think I was crazy.” She’s touching on one of those key barriers to treatment that we often forget to consider: wanting your clinician to see you in a certain way. Sharif was skeptical: “How can she know anything better than I do when I’m the one that’s been coping with this?”

But then, in various ways, each of the kids found treatment that worked. They all talk about this process, and part of the educational value of this movie is hearing them discuss when they learned what OCD was, how they were taught to see their thoughts differently, and what did or didn’t work for them. Jake started out in a group, where he learned that other people had similar symptoms. Ariel started out doing intensive treatment six hours a day, but quickly got better. And Sharif began purposely doing things imperfectly until he could habituate to the anxiety. There’s a wealth of information about each person’s hierarchy and exposures, but the film does seem to rush the part about treatment a little bit. It would have been interesting, for one thing, to hear from the same siblings again about how treatment ended up making things easier.

One thing that really stands out near the end is Vanessa saying, “I don’t think it ever really goes away. It’s always in you. It can just happen out of nowhere, where you’ll just get a blast and you just kind of have to work through it.” I’m not sure whether or not OCD forces kids to become wiser a lot younger than they normally might, but this kind of readiness to accept life’s difficulties without lashing out at them seems pretty uncommon among ten-year-olds.

“Learn about overcoming OCD from the experts”

The filmmakers’ most important choice, and the crux of the film, is to reposition the six kids as the real experts. In most mental health media, the patient perspective is entirely absent. When it’s not absent, it feels canned or at least formulaic as people feel compelled to talk about their experiences in the same narrow terms, over and over. This creates a vacuum for people who are trying to figure out why they’re struggling so much and only finding the same old ideas everywhere.

As for the usual experts, there’s a ton of content out there from clinicians and researchers, and that stuff is always important. But we don’t hear often enough in unfiltered terms about mental health from the people who have struggled with it. This is especially true of kids, whose experiences tend to get trivialized or silenced by parents whose worry comes to eclipse their own.

By leaving the explanatory work to the kids instead of always cutting away to a team of experts, as most documentaries would, UNSTUCK gives us the clinical background and the real personal stories all wrapped into one. We get mental health in motion, not in the controlled environment of a research study. The movie is clearly informed by all of the necessary science, and a few clinical advisors appear in the credits, but the experiential stuff never feels dominated by clinical concerns.

It’s refreshing to hear these precocious young people courageously examine their own journeys, but this doesn’t mean the movie is full of unstructured venting about how hard it is to deal with OCD. Even more common than the overly clinical stuff about OCD is the kind of disorganized, repetitive internet content that never seems to lead anywhere. UNSTUCK stays away from this the same way it stays away from being too cold and clinical: by trusting the kids to relay their own stories, instead of imposing certain lessons or motifs (these emerge naturally as similar symptoms and treatment decisions are discussed).

The kids are insightful and well-informed, and have a well-earned sense of humor about their own symptoms. Sometimes the amount of clarity and honesty they bring to their assessment of how their behavior has affected them and their families is almost jarring; it makes me wonder why it took so long for someone to make a movie like this.

Final Thoughts

UNSTUCK is a moving and informative short documentary that will be a great help to anyone hoping to understand OCD, particularly in children and adolescents. If you want to teach other people about OCD and some of its many manifestations, showing them this movie would be a great choice. It’s also a great antidote to the endless toxic stuff about OCD across the internet and in our culture more generally. And as a supplement to reading clinical perspectives, it offers a much-needed experiential take on mental health.

If you’re worried about this kind of thing, there are parts of the movie that can be sad. You’re watching kids talk about emotionally trying experiences, so that’s sort of a given. But the overall tone is hopefulness, and it comes from a firm commitment to the belief that feeling better is quite possible.

As a self-help tool, this movie will help you understand OCD and will give you some hints about how to get better, but it isn’t a treatment method. This isn’t the goal of the film, but it’s worth mentioning that you shouldn’t go into it hoping your own symptoms will improve. At the same time, learning about other people’s struggles can be cathartic. It’s worth noting that the struggles that OCD creates for these kids are barely different, if at all, from those that adults with OCD face. This is not really, in the end, a movie about kids with OCD. It’s a movie that sees kids as the best spokespeople for what it’s like to have OCD, and it makes a powerful case.

The movie is available now for educators and groups, and will be released soon for everyone else. In case you haven’t seen them already, the trailers are compelling. Here’s one of them:

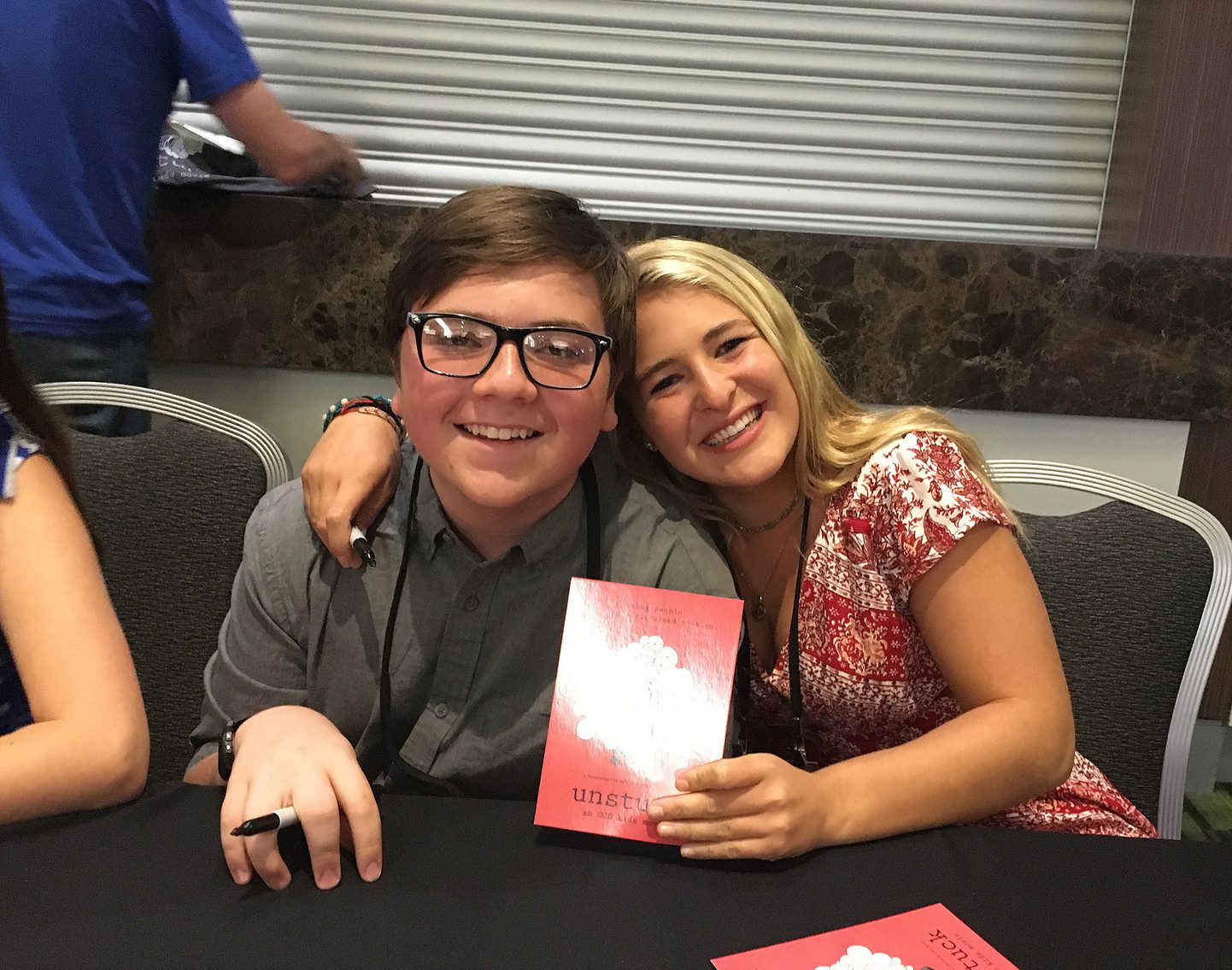

The close attention evident in each shot of this film can be explained in part by the fact that both its director (Kelly Anderson) and its producer (Chris Baier) are parents of kids with OCD. Kelly and Chris began to work on the film after meeting at a support group in New York, and clearly carried their determination to help their own children into their work on this film. Their care in bringing awareness to a disorder affecting hundreds of millions around the world is admirable.

And then we have the real stars of UNSTUCK: the eight young people (six with OCD and two siblings) who bravely tell us about all aspects of life with obsessive-compulsive disorder. You can’t watch this movie without admiring how they’ve responded to their condition by learning about it and committing to dealing with it differently.

Be sure to keep an eye on the film’s website for updates on how to watch it as an individual. If you’re lucky enough to catch it at a festival or community screening, let us know what you think. You can also check out UNSTUCK on Facebook.

And, as a bonus, check out Chris Baier and his daughters talking about the documentary (and life with OCD) on Stuart Ralph’s The OCD Stories podcast.

If you happen to know of a parent whose child is struggling with OCD, let them know that they can schedule a free call today with the NOCD clinical team to learn more about how a licensed therapist can help. ERP is most effective when the therapist conducting the treatment has experience with OCD and training in ERP. At NOCD, all therapists specialize in OCD and receive ERP-specific training.