This is a guest post by Jackie Shapin, a licensed Marriage and Family Therapist who specializes in anxiety, OCD, and eating disorders.

There are many different ways of reacting and responding to obsessions – those unwanted intrusive thoughts, feelings, images, or ideas that increase distress and anxiety. While some responses are only temporarily helpful or unhelpful altogether, others can make a long-term, positive impact. Knowing the difference is important for both people who struggle with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and professionals working to help therapy members manage their intrusive thoughts in a meaningful way.

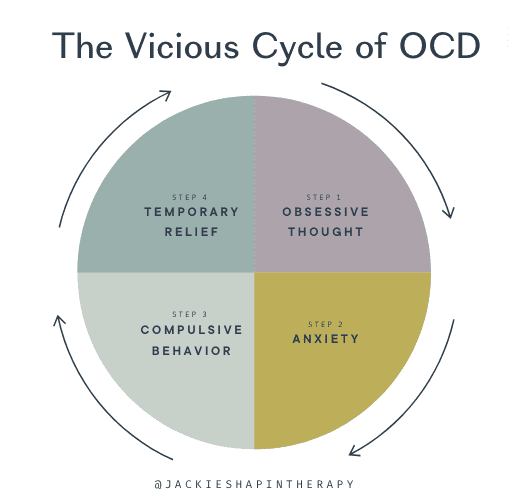

Remember that OCD is a cycle that starts with an obsession and the distress it creates. Naturally, we want to feel better, so we often do something to try and reduce that anxiety. Compulsions – the other side of the OCD coin – is the brain’s attempt to do just that. The problem is that compulsions are repetitive, time-consuming, and only provide temporary relief; the same obsession that started the cycle and the ritualistic urge to find relief from it can come back minutes, hours, or days later. This is why the cycle repeats, and why breaking it is vital to truly managing OCD.

While we cannot control or get rid of our intrusive thoughts or the feelings they bring up, what we can control and have a choice over is what we do next.

Therapists who do not have specialized OCD training may unknowingly utilize unhelpful responses to compulsions in an attempt to alleviate distress, including thought stopping, thought suppression, challenging obsessions, distraction, or relying on talk therapy alone. These tactics can provide temporary relief, but they can also become compulsive in nature because they fail to break the OCD cycle. To make a lasting difference, you have to help change the brain’s pattern by teaching it that you do not have to utilize compulsions. One way to do that is by resisting the urge to do anything that temporarily makes anxiety and distress go away.

Community discussions

Response Prevention

Exposure and Response Prevention is an evidence-based treatment for OCD. Here, I am not focusing on exposure, but rather on what happens after someone has been triggered by or exposed to their fear – be it real or imagined – and once their anxiety has increased as a result. Response Prevention involves willingly choosing to do “nothing” in the face of obsessions; choosing not to respond in ways that keep the unhealthy pattern going. When done correctly, it is one of the most important parts of OCD treatment.

When it comes to obsessions, doing “nothing” in response can be very difficult. Even if the goal of OCD recovery is to allow obsessions to be there without doing anything about them, I believe this to be a choice that takes practice. For the purposes of this article, I will use the word “respond” to explain five tools I use most often to help the people I work with cut out compulsions. I am specifically not using the term “react” because a reaction is automatic, fast, easy, unconscious, and often fuels more reactivity and stress. A response, on the other hand, is intentional, slow, requires attention, and creates more connection and space.

When thinking about these tools, it’s also important to consider the difference between distraction and healthy redirection. Distraction involves escaping unpleasant situations, thoughts, or emotions. Healthy redirection, which I advocate for, involves consciously directing your attention and energy toward your values and what you want to be doing.

Five Tools To Cut Compulsions

Psychoeducation

Learning about OCD can be life-changing for someone who has it. On average, it takes 14-17 years for someone to be correctly diagnosed with OCD. When they finally do, it can feel relieving to know that they’re not alone, that OCD is a disorder, and that there are ways of managing it. Learning about what OCD is, how it’s diagnosed, the OCD cycle, the OCD brain, and different research studies can alone help reduce symptoms. For this reason, it is critical that psychoeducation is not left out of treatment. It is also important for someone to learn how and why OCD treatments work. This can increase and maintain motivation to do the work needed for recovery. I wouldn’t want anyone doing what I told them to do just “because I said so.”

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is the non-judgmental observance of thoughts while coming back to the present moment. When we become more mindful of our present moment, we can increase our awareness of when OCD gets triggered. Awareness is key in recovery because we can’t change the cycle if we aren’t able to notice it. Start by becoming aware of your intrusive thoughts. Notice the distress that comes, how this feels in your body, and what you do about it. Then name it. For example, “I am noticing that I am having intrusive thoughts. I’m feeling anxious. My heart is racing, my hands are sweating, and I feel a tightness in my chest. Now I notice I am doing that thing where I spiral and go over everything I just did.” This naming practice will help slow you down, increase insight into your OCD cycle, and create space for you to shift how you respond to your thoughts and feelings.

Thought Defusion

Thought defusion techniques are primarily used to detach, separate, or get some distance from thoughts and emotions. They can help reduce the meaning you give your thoughts and can allow you to distance yourself from the fear that comes with them. Thoughts and feelings are not facts. Just because we have them does not make them true or productive. It can be hard to remember this when obsessions and distress happen so quickly. Compulsions can also happen fast, but that does not mean they are impossible to slow down or resist. The next time you recognize an obsession, I want you to start saying, “I am noticing I am having the thought that…”

Doing this exercise may not feel like a big step, but I promise you: it helps separate yourself from your thoughts. Try doing this so much that it becomes annoying! That’s one way to know you’ve practiced it a lot. Some other thought diffusion techniques that can be fun include word scramble: take an intrusive thought or word and play with the letters to make as many words as you can. This exercise is a reminder that thoughts are just a bunch of letters that make words and sentences. Singing your intrusive thoughts or saying them with a silly voice can also be an amazing way to diffuse obsessions. Anything that breaks the hold obsessions have over you—even momentarily—is helpful. Even if these exercises sound ridiculous to you, try them anyway. If something can create pause from your distressing and often irrational obsessions, it’s worth it.

Attention versus Awareness

We cannot control what is in our awareness, but we can control what we direct our attention towards. We cannot make our thoughts or feelings go away, but we can choose what we want to focus on. This does not mean you are ignoring your thoughts or distracting yourself. Notice what’s occupying your attention, acknowledge it, then ask yourself, “What do I want to pay attention to?” This will take redirecting, at times, and that is okay!

Putting this into practice can sound like, “I am noticing I am having thoughts about my parents dying. These thoughts probably won’t go away. I am going to allow them to be there and let my attention wander. Man, I need to get my homework done…” Thoughts will remain in your awareness. Let them be there, because if you try to fight them, they will only get stronger. You do not have to choose what you pay attention to, but you can redirect to what you want to attend to. To learn more about this technique, check out Dr. Michael Greenberg’s article “How to Stop Paying Attention.”

Non-Engagement Responses

Lisa Levine, Psy.D. created non-engagement responses (NERs), which she describes as “statements that purposefully affirm the presence of the anxiety or uncertainty OCD insists you run away from.” NERs allow you to respond to your OCD in a way that allows you to actively disengage. These responses allow you to face your fears proactively without engaging in OCD’s attempts to get you to ritualize.

When you agree with OCD, there is no avoidance, escape, reassurance-seeking, attributing meaning, or mental reviewing. You are facing your obsessions and doing something proactive. NERs, says Levine, “empower you to assert yourself in a way that makes it impossible for OCD to successfully draw you in and engage you.”

Think of it like responding to a bully. If you show a bully you are afraid or try to fight back, they are likely to up the stakes. If you agree with a bully, the bully won’t win. If a bully doesn’t win, they get upset and leave you alone. Don’t show the OCD that you are upset. If you strategically agree with whatever the bully is trying to taunt you with, rather than becoming defensive and arguing back, it becomes much more difficult for the bully to continue getting you to engage with its insults and threats/baiting you to argue. Agreeing, in this case, does not mean you are agreeing that a fear is going to happen, but rather that it is possible. NER’s can be anything that has some agreement to it. Four specific responses that I highly recommend reading more about include Affirmation of anxiety, Affirmation of uncertainty, Affirmation of possibility, and Affirmation of difficulty.

What is so great about these five tools is that they give you the ability to do something when doing nothing just doesn’t feel possible. Your goal should never be to get rid of obsessions, and these tools will not work if that is the goal you have in mind. Focusing on getting rid of obsessions only allows them to get stronger.

Remember that while these tools might not always feel like they are “working,” it is important to try different strategies to resist compulsions. Experiment with them; see what works and what doesn’t. Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist, Kimberly Quinlan coined the adage, “It’s a beautiful day to do hard things.” She is right! Even though these approaches can feel hard because they don’t immediately rid you of discomfort, they truly do work in the long run. The more you are able to allow the discomfort and anxiety to exist, the more you are teaching your brain that you can handle anything without compulsions.